What Is Proof Of Stake? And How Does It Work?

Introduction

In a blockchain network where participants remain anonymous, a dependable coordination mechanism is essential. The “proof” acts as confirmation that a participant has met the requirements to validate a block of transactions, signifying their good-faith participation. One such consensus algorithm employed to generate new blocks, distribute new cryptocurrency, and validate transactions is proof of stake (PoS).

This mechanism provides an alternative to the original consensus method, proof of work (PoW). Rather than the energy expenditure necessitated by PoW, PoS requires validators or miners to make contributions to the network from their own holdings of the blockchain’s native cryptocurrency, i.e., their “stake.”

To avoid losing their stake, validators are incentivized to operate honestly and reach a consensus on the order and validity of transactions. PoS miners are selected based on the amount of cryptocurrency they hold or “stake” in the network; therefore, the more cryptocurrency a validator stakes, the more likely they will be chosen to create the next block.

Read More >> Technical Guide To Proof Of Stake

Comparison With Proof Of Work

Instead of stakes, PoW requires considerable computational resources and energy consumption to validate transactions and create new blocks. For this reason, people assume proof of stake is more energy efficient and less resource intensive than PoW. Yet, we will learn later in this article that this is a somewhat false assumption.

Both consensus mechanisms aim at producing new blocks and validating transactions. They must also maintain the security and integrity of the blockchain network, but they do so in different ways.

In PoW, miners compete to solve the Byzantine Generals’ Problem faster and reach a consensus on the validity of transactions. The quickest miner to complete the target hash creates a new block and receives the block reward, the network’s token of value. By selecting the chain with the most work, the network overcomes any ambiguity, and double spending is prevented due to requiring at least 51% of the global hash power for a double spend block to catch up.

In Ethereum’s PoS, by means of comparison, the double-spending problem is solved using “checkpoint blocks” at various points in time, approved by a two-thirds majority vote through a stake to “assure” everyone in the network about the “truth” of the system.

Another significant difference between PoS and PoW is the incentives and the ethics behind them. In a PoS network, incentives hide a negative (penalty-based) connotation since validators may lose their stake if they act maliciously. This contrasts with PoW, where miners are only incentivized to behave honestly to be rewarded with cryptocurrency through a positive (reward-based) incentive system.

Bitcoin miners who attempt to break the rules by producing poorly formatted blocks or invalid transactions will find their blocks ignored by full nodes. As a result, they will incur substantial electricity costs. Moreover, they would need to command 51% of the hash power to build upon older blocks; otherwise, these chains will lag behind, leading to even more costly energy waste.

One of the most heated debates in consensus mechanisms is decentralization and the ability to maintain this decentralization. PoW decentralization is secured by an active network of full nodes, in addition to miners, a vital feature that isn’t reflected in PoS consensus mechanisms. The importance of nodes in PoW was marked in the blocksize war of 2017 when the small block supporters won the battle against big blockers by starting the user-activated soft fork (UASF) movement and voting for the BTC chain instead of Bitcoin Cash (BCH). That historic Bitcoin event emphasized how nodes could win against big corporations and that miners do not control the network, unlike PoS validators.

How Proof Of Stake Works

In a proof-of-stake network, participants can be miners or validators who verify and authenticate transactions and create new blocks based on the amount of the blockchain’s native cryptocurrency they hold or “stake” in the network.

Validators are randomly selected to add the following block based on their stake; the more cryptocurrency a validator has staked, the more likely they will be chosen to validate transactions and create new blocks.

When a validator is chosen to create a new block, they need to validate all the transactions in the block and add them to the blockchain. To validate the transactions, the validator must check that they are valid, are not “double spending,” and that the sender has enough cryptocurrency to make the transaction.

Once all transactions are validated in the block, a new block is created and added to the blockchain. At that point, the successful validator is rewarded with native tokens for their work.

In a proof-of-stake network, consensus is achieved when most validators agree on the state of the blockchain. If a validator creates a block that is not accepted by the majority of validators, the block is rejected, and the validator may lose their staked cryptocurrency.

Valid Criticisms Of Proof Of Stake

Although proof of stake is often perceived as more energy efficient and less resource demanding when compared to proof of work, these assumptions can be easily refuted, showing that decentralization and security are compromised with proof of stake and that PoS is a mirror image of the current monetary system, which is known to be particularly energy inefficient, as well as unfair to the majority of participants.

One key argument against the perceived advantages of proof of stake is the concentration of wealth and power this can lead to. In a PoS system, validators with more stake (or wealth) have a higher probability of being chosen to validate transactions and create new blocks. This results in a rich-get-richer scenario, where the wealthiest validators gain even more control and influence over the network. The table below from Nansen Research provides a clear picture of the staking landscape within the Ethereum proof-of-stake system.

This concentration of power contradicts the principles of decentralization, as a small number of validators can potentially dominate decision-making processes. Unlike proof of work, where miners have to invest in computational power, proof of stake allows validators to accumulate wealth and control the network based on their initial stake, rather than their ongoing contributions to the system.

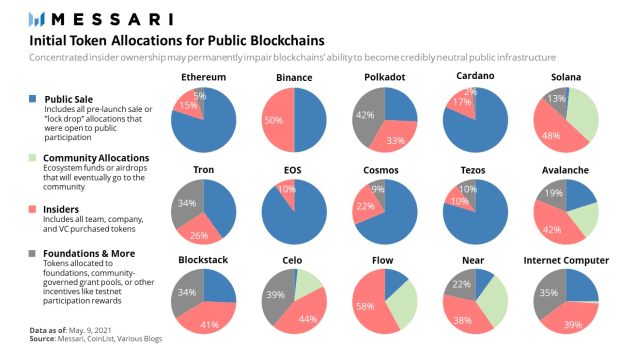

Another valid criticism of proof of stake is the pre-mine configurations many cryptocurrencies, including ether (ETH), are based on. Mining tokens before their public launch means that founders, stakeholders, and developers may access a lot of wealth and have a considerable advantage over any other investors or validators who later join the network. While such a design could also apply to proof-of-work blockchains, it is more often used in the proof-of-stake ecosystems, because in such systems, it’s possible to have a greater share of the validation process, due to the absence of nodes.

Common critiques of the PoS consensus mechanism:

- Lack of decentralization: validators who hold a large amount of cryptocurrency have a higher chance of being selected to create new blocks, receive rewards, and they have more influence over the network, leading to a concentration of power in the hands of a few validators. This could lead to a situation where a small group of validators controls the network and its rules, potentially compromising its security and decentralization and reinforcing existing wealth inequalities.

- The validation process can be manipulated: since the network could be manipulated by owning 51% of the tokens in circulation, it is easier to influence the transaction validation than with a 51% attack on PoW, which requires controlling 51% of a network’s current computational power.

- Security: in PoS, the network’s safety depends on the amount of cryptocurrency held by validators, making it more vulnerable to attacks if a large number of validators were to collude.

- Complexity: there are various types of proof of stake, such as delegated PoS (DPOS), leased PoS (LPOS), pure PoS (PPOS), and other hybrid types. These are all variants of an overengineered system, which is difficult for anyone to truly explain and understand. The more complex a system is, the more likely it is to fail.

- Environmental impact: proof of stake (PoS) is often criticized for its environmental impact, mirroring the concerns associated with the existing monetary system. Unlike proof of work (PoW), which incentivizes the expenditure of energy, PoS systems are considered less energy intensive. However, the proliferation of blockchains relying on inefficient PoS mechanisms collectively exacerbates their environmental footprint.

- Nothing-at-stake problem: the nothing-at-stake problem is a theoretical weakness in PoS, where validators have little to lose by creating multiple versions of the blockchain. In a PoS network, validators could create multiple versions of the blockchain, hoping that one version will become the “correct” version. This could lead to a situation where the network is unable to reach a consensus, compromising its security.

- Difficulty in determining the right amount to stake: determining the optimal amount of cryptocurrency to stake in a PoS network is challenging. Validators must balance the desire for higher rewards with the risk of losing their stake.

Would Bitcoin Ever Move To Proof Of Stake?

Ethereum’s recent shift from PoW to PoS in September 2022 sparked ideas across the corporatized environmental world that Bitcoin should do the same and therefore abandon the “extreme energy consumption” required by its consensus mechanism.

Changing Ethereum to a PoS system won’t/didn’t reduce energy consumption by 99.95%, as it fails to take into account that expensive enterprise farms and corporations use enormous amounts of energy to subsidize the work necessary to complete PoS transactions globally.

The Greenpeace “Change the Code” campaign funded by Ripple Labs to discredit the energy usage of Bitcoin’s proof-of-work system is a typical example of how the corporate world does not encourage change and, instead, promotes the perpetration of an elitist system that is now fully mirrored in Ethereum’s consensus mechanism.

Besides proposing a new revolutionary and fair monetary system, PoW fosters renewable energy innovation and the use of stranded and wasted energy which will benefit the environment more than a supposedly energy-efficient PoS system in the long term. Proof of stake is merely better at concealing the energy purchases made by the corporations that enable its validating mechanism.

Thankfully, Bitcoin’s code is highly resistant to these types of attacks and was purposely developed this way. It is improbable that a proposal to change the code would even pass any initial stage of consideration by the developers, let alone the community.

Conclusion

In free markets, it is important to allow both proof-of-work (PoW) and proof-of-stake (PoS) mechanisms to coexist and evolve in ways that are profitable and beneficial to their respective supporters. Bitcoin, as an innovative monetary system, not only brings about technological advancements but also strives to have a positive impact on the environment. Educating individuals about the significance of PoW in this transformative process is a responsibility that Bitcoin enthusiasts understand and embrace.

If you’re concerned about wealth protection, financial inclusion, and fostering a better environment for all life on earth, the ideal choice is a currency that is borderless, permissionless and embodies pristine hard money and freedom technology.

This type of money, which is impervious to censorship and safe from confiscation, highlights the superiority of proof of work over proof of stake. In years to come, Bitcoin may likely be the only token of value, and the decision to support proof of work will be seen as obvious in hindsight.

Credit: Source link